Emigrant Trail

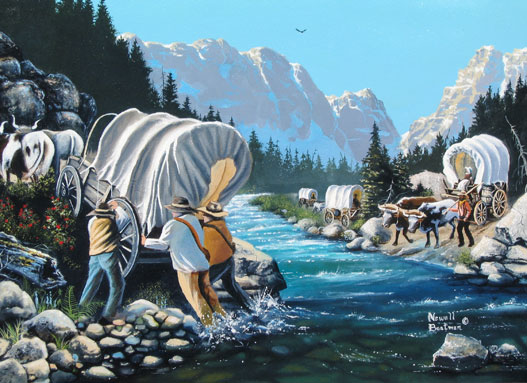

The group that had been working in the Sutter’s Fort area met with Capt. John Sutter on April 9, 1848, to settle their affairs. Sutter paid the men mostly in kind, with horses, livestock, wagons, seeds and the other things they would need. The men tried to leave in early May. The existing Old California Trail went from Sutter’s Fort north to Johnson’s Ranch (now Marysville) and then east to Emigrant Gap, Truckee Lake (now Donner Lake), along the Truckee River to present day Reno, Nevada. The snow was too deep and they were unable to make the trip over the Sierra Nevadas.

It was decided that they would find a place of gathering and would assemble the group later to again try to leave. The California Trail had the disadvantage of requiring teams and wagons to cross the Truckee River some twenty seven times and was very difficult, so the group decided they would try to find a better route when they were able to leave. June 17, 1848, Henry Bigler and two others set out to select a place of gathering. They found a place they called Pleasant Valley (still named that today) and June 21, 1848, the group began to assemble for their planned departure of the area.

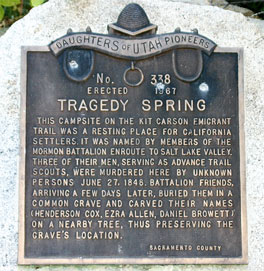

Daniel Browett was elected Captain of the company. Browett decided to ride out and scout a possible route with the help of Ezrah Allen and Henderson Cox. The main body did not want them to go, but they felt it was necessary and went anyway. The group kept waiting for the three to return, but by July 1st they had not come back and the group felt they could wait no longer for them.

Sly Park today

The group, which consisted of 47 men, at least one woman, 17 wagons, 150 horses/mules, and 150 cattle, moved out on July 3, 1848. They moved east along the ridge toward the area occupied by a forward group with Capt. James C. Sly. This meadow is now under Jenkinson Lake created by the Sly Park Dam. The area was named Sly Park, after James Sly, referring to the meadowed area as “Sly’s Park.” As they approached the area, they heard one of the cannons the group had obtained from Sutter being fired. The forward group was celebrating July 4th, by firing it. By July 10th the group had all arrived in the Sly Park Area and built corrals for the cattle, which were wandering off while grazing in the meadow. Ten men were sent forward to look for the missing scouts.

The group, which consisted of 47 men, at least one woman, 17 wagons, 150 horses/mules, and 150 cattle, moved out on July 3, 1848. They moved east along the ridge toward the area occupied by a forward group with Capt. James C. Sly. This meadow is now under Jenkinson Lake created by the Sly Park Dam. The area was named Sly Park, after James Sly, referring to the meadowed area as “Sly’s Park.” As they approached the area, they heard one of the cannons the group had obtained from Sutter being fired. The forward group was celebrating July 4th, by firing it. By July 10th the group had all arrived in the Sly Park Area and built corrals for the cattle, which were wandering off while grazing in the meadow. Ten men were sent forward to look for the missing scouts.

July 12th they built an additional corral for the horses. July 14th the 10 men returned with no sign of the missing scouts. The group moved out on the 15th and followed the ridgeline as best they could. They made about 8 miles that day and camped at a place they called “Log Springs.” (This was east of the present reservoir). About two miles from Log Springs, the road turns due east and follows what is now paved Mormon Emigrant Highway. At this point is a 203-foot ponderosa pine tree, known as the “49er Tree.” This use to have a blaze on the side with an arrow pointing to the right for directing the gold seekers. Recent vandalism has burned the arrow and the blaze, but the tree is still standing.

July 16th was another day like the previous one, with men clearing brush and moving rock off the trail. They camped that night at “Camp Creek.” (Still known by that today).

July 17th, they cleared about 10 miles of bad area for the trail and camped at “Leek Springs” which had vegetation that resembled leeks. It is still known by that name today. Azariah Smith and others brought the horses and livestock up from Sly Park to this area on this day. Henry Bigler and three others went about 10 miles ahead clearing brush for the trail. On the way, they had seen some Indians on horseback that were wearing clothes that resembled those of the missing scouts. They also found a campfire area near a large spring and what appeared to be a freshly dug grave. While in this location they organized into captains of ten and appointed Samuel Thompson, as captain over the entire group, with Jonathan Holmes, as president. After seeing the Indians, they posted a guard all night for the first time.

On Wednesday, July 19th they rolled out of Leek Springs. They were only able to make about 5 or 6 miles that day and camped by the large spring with the fresh grave. Tragedy GravesiteThe grave was opened and they found the naked bodies of Browett, Allen, and Cox. One of them had been hit in the face with an axe and shot in the eye. There were bloody broken arrows and bloody rocks in the brush around the site. They also found Allen’s double gold pouch with about $100 worth of gold in it. Allen always wore the pouch around his neck and it was felt that during the night attack and trying to rip the clothes off him, that it must have fallen, unnoticed, into the brush. The group called this place Tragedy Spring, because of this sad incident, and laid over another day to dig a deeper grave, built a rock cairn and carve a memorial plaque in a pine tree nearby. It had taken them 15 days to blaze the trail of 39 miles from Pleasant Valley.

On Wednesday, July 19th they rolled out of Leek Springs. They were only able to make about 5 or 6 miles that day and camped by the large spring with the fresh grave. Tragedy GravesiteThe grave was opened and they found the naked bodies of Browett, Allen, and Cox. One of them had been hit in the face with an axe and shot in the eye. There were bloody broken arrows and bloody rocks in the brush around the site. They also found Allen’s double gold pouch with about $100 worth of gold in it. Allen always wore the pouch around his neck and it was felt that during the night attack and trying to rip the clothes off him, that it must have fallen, unnoticed, into the brush. The group called this place Tragedy Spring, because of this sad incident, and laid over another day to dig a deeper grave, built a rock cairn and carve a memorial plaque in a pine tree nearby. It had taken them 15 days to blaze the trail of 39 miles from Pleasant Valley.

On July 21st, they made a journey of about four miles and camped at Rock Creek, in Rock Canyon. They stayed in this spot for a couple of days, while men worked on the road to the top of the mountain, where they found snow up to 15 feet deep. Henry Bigler reported he was scooping up snow with one hand, while picking wildflowers with the other. Blazing the road was a difficult project and they reported that the water would freeze about 2 inches in their buckets at night. Zodock Judd recorded in his journal that they were encountering granite boulders up to 8 to 10 feet in diameter and they had no hammers or drills to break them up. Finally someone suggested they build a fire on top of the boulders and when they did and then let the rocks cool, they would crumble and were easily removed. They were kept busy with replacing broken axles, etc. and the blacksmith with welding broken metal parts.

On July 21st, they made a journey of about four miles and camped at Rock Creek, in Rock Canyon. They stayed in this spot for a couple of days, while men worked on the road to the top of the mountain, where they found snow up to 15 feet deep. Henry Bigler reported he was scooping up snow with one hand, while picking wildflowers with the other. Blazing the road was a difficult project and they reported that the water would freeze about 2 inches in their buckets at night. Zodock Judd recorded in his journal that they were encountering granite boulders up to 8 to 10 feet in diameter and they had no hammers or drills to break them up. Finally someone suggested they build a fire on top of the boulders and when they did and then let the rocks cool, they would crumble and were easily removed. They were kept busy with replacing broken axles, etc. and the blacksmith with welding broken metal parts.

On July 24th, they left Rock Creek to cross over the top of the mountain. The road was very rough. One of the wagons tipped over twice with the steep grade and many of the others broke down. They crossed over West Pass, at an elevation of 9,550 feet. This would be the highest wagon pass in the continental United States. (In 1994, the Oregon Trail Association, Sons of Utah Pioneers, Daughters of Utah Pioneers, and the forest service would dedicate the peak just south of West Pass as Melissa Coray Peak, after the only known woman accompanying the group.)

On July 26th, after laying over two days to repair wagons, and after traveling a distance of 6 miles, they descended and camped near a lake, which they called Lake Valley. (This is believed to be present Woods Lake). They laid over another day here to do repairs, while some went ahead to scout the best route out of the mountains.

On July 28th, they moved east through the area now known as Carson Pass, where Capt. John C. Fremont and his guide, Kit Carson, had crossed 4 years earlier. On February 14, 1844, Kit Carson had carved his name on the side of a pine tree in the pass, which was at an elevation of 8,600 feet. A large corral was built to hold all of the animals, while they worked at lowering their wagons down the steep slopes with sharp drop offs. This sharpest drop off there would become known during the gold rush period as the “Devil’s Ladder,” because of the difficulty getting wagons and teams past it. They would use block and tackle with ropes wrapped around trees to lower the wagons down the steep slope. (Some of the journal entries during the gold rush era talk about as many as 250 wagons waiting their turn to be assisted up this area of the trail.)

On July 28th, they moved east through the area now known as Carson Pass, where Capt. John C. Fremont and his guide, Kit Carson, had crossed 4 years earlier. On February 14, 1844, Kit Carson had carved his name on the side of a pine tree in the pass, which was at an elevation of 8,600 feet. A large corral was built to hold all of the animals, while they worked at lowering their wagons down the steep slopes with sharp drop offs. This sharpest drop off there would become known during the gold rush period as the “Devil’s Ladder,” because of the difficulty getting wagons and teams past it. They would use block and tackle with ropes wrapped around trees to lower the wagons down the steep slope. (Some of the journal entries during the gold rush era talk about as many as 250 wagons waiting their turn to be assisted up this area of the trail.)

Saturday night of July, July 29th, found them camped at Red Lake, after descending the steep Carson Pass area. They traveled about 5 miles down Hope Valley on Sunday July 30th, which they had named because their journals said it was the first real sign of hope that they would get out of the mountains. The valley still called that today. They camped at Pass Creek, at the head of a 15-mile long canyon. It took them most of the week to cut the trail through some of the most difficult territory yet. The mountains rose several hundreds of feet on each side of the canyon. While they were working on this section, it snowed on them. They also had a group of 13 former Mormon Battalion members with pack animals ride into their camp. These riders had left the mines near Pleasant Valley and made the entire trip in 5 days over their new trail.

Saturday night of July, July 29th, found them camped at Red Lake, after descending the steep Carson Pass area. They traveled about 5 miles down Hope Valley on Sunday July 30th, which they had named because their journals said it was the first real sign of hope that they would get out of the mountains. The valley still called that today. They camped at Pass Creek, at the head of a 15-mile long canyon. It took them most of the week to cut the trail through some of the most difficult territory yet. The mountains rose several hundreds of feet on each side of the canyon. While they were working on this section, it snowed on them. They also had a group of 13 former Mormon Battalion members with pack animals ride into their camp. These riders had left the mines near Pleasant Valley and made the entire trip in 5 days over their new trail.

On August 5th, they emerged out of the canyon into the Carson Valley. From there the trail went north and joined the established California Trail, at present day Wadsworth, Nevada.

On August 5th, they emerged out of the canyon into the Carson Valley. From there the trail went north and joined the established California Trail, at present day Wadsworth, Nevada.

It had taken them over 30 days to blaze the trail of approximately 170 miles over the Sierras, that would become known as the “Mormon Carson Emigrant Trail.” It would be used the following few years by over 50,000 wagons and over 200,000 gold seekers, coming to the gold fields during the gold rush, which started in 1849. Traffic would be so heavy during the 90 day snow-free travel period, that according to some of the journals, it would be hours before there would be a break big enough between wagons to cross from one side of the trail to the other. The records for the summer of 1854, beginning July 1, 1854, show that even 5 years later, there were 800 wagons, 30,015 head of cattle, 1,903 horses/mules, and 8,550 sheep that came over the trail that season. There would be 40 overnight accommodations and trading posts between Nevada and Old Hangtown. That means that there was a stopping facility every 3 to 4 miles.

This advance group of former members of the Battalion finally reached the Valley of the Great Salt Lake September 28, 1848. Ezrah Allen’s pouch of gold finally found its way to his wife Sarah, in Council Bluffs. She saved enough of it to make her a wedding ring and used the rest to buy a wagon and team to bring her children to Utah.