Bear Flag Revolt

The Bear Flag Revolt and William B. Ide

THE SETTING:

Alta California was without a strong presence of Mexican authority in 1846. Instead, power was welded by shifting alliances among the local families, who were California-born but of Spanish blood, and who considered themselves distinct from Mexicans. These “Californio” families drew their wealth from their vast land holdings: General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, for example, in 1846 had a private estate of over 175,000 acres.

Alta California was without a strong presence of Mexican authority in 1846. Instead, power was welded by shifting alliances among the local families, who were California-born but of Spanish blood, and who considered themselves distinct from Mexicans. These “Californio” families drew their wealth from their vast land holdings: General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, for example, in 1846 had a private estate of over 175,000 acres.

By the 1840s, the Californios had come to realize their days as the ruling power were numbered. In 1844, the United States had elected James K. Polk as President on a platform that espoused “Manifest Destiny” — the expansion of the U.S. to its “natural” western boundary of the Pacific Ocean. Added to this concern was the simmering dispute between the U.S. and Mexico over Texas. There was also concern over British and French ambitions in the Pacific, and Russia’s expansion from Alaska.

Until the 1840s, most of the small number of Americans in California were sailors, traders or pathfinders. What few American settlers there were had most likely come by sea, around Cape Horn. But beginning in 1841, large numbers of Americans set out from Missouri in wagon trains for the long and dangerous trip west. Many of these people were inspired to make the journey by the writings of John Marsh, whose articles extolling the beauty and abundance of Alta California had been published in many Eastern papers. It is estimated that by 1845, there were more than 800 Americans in Alta California, more than enough to concern the Californio families.

The ambitious and aggressive Americans were viewed as a threat to the established order. Although land ownership was limited by law to those who held Mexican citizenship and were Catholic, many Americans got around this simply by taking the necessary oaths and converting – at least in name. In the fall of 1845, however, rumors circulated throughout Alta California that the Mexican authorities would soon disallow any further conversions and that Mexico was planning to expel all American settlers once the spring thaw cleared the passes in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

THE BEAR FLAG REVOLT & WILLIAM B. IDE:

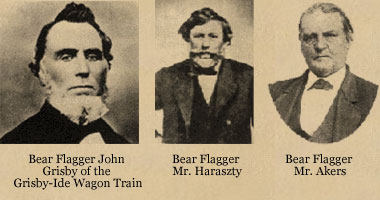

William Brown Ide, his wife Susan B., and their five children (4 other children had died) left Missouri on April 1, 1845. Ide had been an Elder in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and was President of a Branch of the Church in Illinois. He had also served on the delegation at the convention to promote Joseph Smith, Jr. for candidacy for President of the United States in February of 1844. He helped drafted the platform for that convention. After Joseph Smith, Jr. was killed in June of 1844, William apparently decided to go west. In the Spring of 1845, the Ides were part of a wagon train, called the Grisby-Ide Wagon Train, bound for Oregon Territory. When the Ides reached Fort Hall (in present Idaho), they were convinced by Caleb Greenwood, an old mountain man, to go to California instead. Greenwood had guided the first wagon train to California in 1844. The Grigsby-Ide party was comprised of about 100 people. They arrived at Sutter’s Fort on October 25, 1845. From there, Ide took his family and went to the Peter Lassen ranch, where they built a sawmill, and then on to the Thomes Ranch, near Red Bluff, where they built a cabin for the winter.

William Brown Ide, his wife Susan B., and their five children (4 other children had died) left Missouri on April 1, 1845. Ide had been an Elder in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and was President of a Branch of the Church in Illinois. He had also served on the delegation at the convention to promote Joseph Smith, Jr. for candidacy for President of the United States in February of 1844. He helped drafted the platform for that convention. After Joseph Smith, Jr. was killed in June of 1844, William apparently decided to go west. In the Spring of 1845, the Ides were part of a wagon train, called the Grisby-Ide Wagon Train, bound for Oregon Territory. When the Ides reached Fort Hall (in present Idaho), they were convinced by Caleb Greenwood, an old mountain man, to go to California instead. Greenwood had guided the first wagon train to California in 1844. The Grigsby-Ide party was comprised of about 100 people. They arrived at Sutter’s Fort on October 25, 1845. From there, Ide took his family and went to the Peter Lassen ranch, where they built a sawmill, and then on to the Thomes Ranch, near Red Bluff, where they built a cabin for the winter.

By June of 1845, rumors were still circulating of the Mexicans planning to drive out the “Americanos.” In order to secure their land rights, Ide and about 30 American settlers, made up of men from the Grigsby-Ide party of settlers, mountain men and explorers, rode to the Mexican military garrison at the pueblo of Sonoma, north of San Francisco Bay.

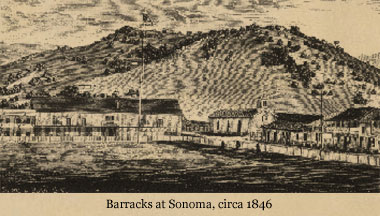

Sonoma was a small pueblo at the time with only about fifty inhabitants. Monterey had been the department seat and had about 700 non-Indian inhabitants, while San Francisco (then called Yerba Buena) had a little over 100 non-Indian inhabitants. Los Angeles had recently become the government seat, but had only a little over 2,000 non-Indian inhabitants.

Early on Sunday morning, June 14, 1846, Ide and his group took over the military garrison without firing a shot. They then went to the home of General Mariano.

Guadalupe Vallejo and pounded on the adobe door; loudly demanded that the General come out and surrender to them. Vallejo quickly donned his dress uniform, then opened the door and invited three representatives of the group in for breakfast and wine. The General’s military bearing and immaculate uniform must have contrasted starkly with the clothing of his “visitors.” Some of the Americans wore buckskins, others wore their work clothes, and still others wore only what rags they had picked up or made during their travels. Robert Semple, a member of the group and later co-publisher of California’s first newspaper, later noted in his memoirs that the party “was as rough a looking set of men as one could imagine.” They told Vallejo they had taken over and a new republic was in control now. General Vallejo offered no resistance and on reading historical account of the time, it appears that he was in favor of the take over as he had been ignored by Mexico City for some time and was even paying his military men with his own money.

Guadalupe Vallejo and pounded on the adobe door; loudly demanded that the General come out and surrender to them. Vallejo quickly donned his dress uniform, then opened the door and invited three representatives of the group in for breakfast and wine. The General’s military bearing and immaculate uniform must have contrasted starkly with the clothing of his “visitors.” Some of the Americans wore buckskins, others wore their work clothes, and still others wore only what rags they had picked up or made during their travels. Robert Semple, a member of the group and later co-publisher of California’s first newspaper, later noted in his memoirs that the party “was as rough a looking set of men as one could imagine.” They told Vallejo they had taken over and a new republic was in control now. General Vallejo offered no resistance and on reading historical account of the time, it appears that he was in favor of the take over as he had been ignored by Mexico City for some time and was even paying his military men with his own money.

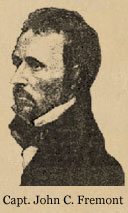

Some of the party then began to have second thoughts. If they were not supported by the United States, Capt. John C. Fremont and the other Americans in California, they would be unable to withstand Mexican Gen. Jose Castro’s forces. There was a move to abandon the town and the whole action they had taken. At this critical moment, Ide stepped forward and exclaimed: “Saddle no horse for me,…I will lay my bones here before I will take upon myself the ignominy of commencing an honorable work, and then flee like cowards, like thieves, when no enemy is in sight. In vain will you say you had honorable motives. Who will believe it? Flee this day, and the longest life cannot wear off your disgrace! Choose ye! Choose this day what you will be! We are robbers, or we must be conquerors!” The party rallied around Ide and declared him “President” of the new Republic of California.

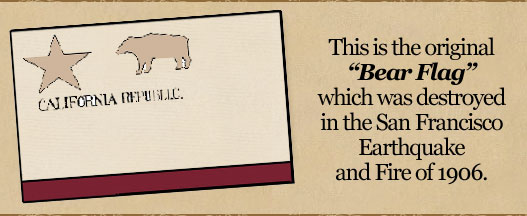

The group made the famous “Bear Flag” and ran it up the flag pole at Sonoma. Since most of the group were hunters and adventurers, they had called themselves the “Osos,” the Spanish word for “bears!” The idea was suggested by William Ford, that a grizzly bear should, therefore, be used as the motto of the flag. The grizzly bear was chosen as an emblem of strength and unyielding resistance. The making of this flag was overseen by William L. Todd, a cousin of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of the future president, and was assisted by Peter Storm. A Californio woman donated a rectangular piece of very light brown muslin about 48” long by 36” wide. Another woman provided a four inch strip of red material and sewed it to the muslin, making a stripe along the bottom reminiscent of the stripes on the American flag. Todd then drew a star in the upper left corner symbolizing the Lone Star of Texas Flag and a crude rendition of a grizzly bear next to it, using for both a brownish mixture of brick dust, linseed oil, and Venetian Red paint. The words CALIFORNIA REPUBLIC were written in black in the middle, to the right of the star. Many reports of the time indicate that the local Mexican kept telling them it looked more like a “Pig” than a “Bear.” Never the less, this crudely-fashioned flag gave this moment in history it’s name: “The Bear Flag Revolt.”

Ide then issued a proclamation setting forth the reasons for the action and developed a platform and declared California an independent republic. Research shows that Ide was able to produce this proclamation in such a short period of time because two years earlier he had helped develop the platform for Joseph Smith’s candidacy for U.S. President and material contained in the two documents are very similar.

Ide then issued a proclamation setting forth the reasons for the action and developed a platform and declared California an independent republic. Research shows that Ide was able to produce this proclamation in such a short period of time because two years earlier he had helped develop the platform for Joseph Smith’s candidacy for U.S. President and material contained in the two documents are very similar.

This action paved the way for the occupation of California by armed forces of the United States. United States Army Lieutenant, John C. Fremont, arrived with his small group of troops on June 25th. On July 5th, the Republic of California, after being in existence for less than a month, was turned over to Fremont. Ide’s forces, the Osos (or Bears), signed on to join forces with Fremont’s group, to form the California Battalion, and Fremont assumed command. Fremont then went on to Sutter’s Fort, to rejoin the rest of his men. On July 2nd, Commodore John Sloat, who had landed at Monterey, aboard the ship, Savannah, announced that the United States and Mexico were officially at war, and raised the American Flag over the customs house there. He sent Lt. Joseph W. Revere, with two American Flags, for Sonoma and Sutter’s Fort. Revere arrived at Sonoma, replaced the Bear Flag and flew the Stars and Stripes there on July 7, 1846.

William Ide finally returned to the Red Bluff area and established his Rancho de la Barranca Colorada (Red Bluff Ranch, so named because of a high red cliff along the west bank of the Sacramento River), and built an adobe house on it. The California-Oregon Trail crossed the Sacramento river at this point and he established a ferry in 1850, which ran for over thirty years and was known as the Adobe Ferry. He was elected Judge of Colusi County (now Colusa, Glenn, and Tehama Counties). He held court in Monroeville, a small town thirty miles south of his ranch. Because the population was so transient, there was a shortage of citizens for public service. In the trial of a horse thief, Ide acted as judge, court clerk, prosecutor, and defense attorney. He raised legal p oints for both sides, mounted the bench and gave his rulings as judge, and then as court clerk, recorded the proceedings. The jury found the defendant guilty, and Ide, as judge, sentenced him to hang. The law at the time stated that the theft of any item, with a value of more than $20, was grand larceny, punished by hanging.

oints for both sides, mounted the bench and gave his rulings as judge, and then as court clerk, recorded the proceedings. The jury found the defendant guilty, and Ide, as judge, sentenced him to hang. The law at the time stated that the theft of any item, with a value of more than $20, was grand larceny, punished by hanging.

Ide died in Monroeville, in December 1852, at the age of 56, after an illness from smallpox that only disabled him from the duties of his office for about one week. In his short, seven year period in California, in addition to County Judge for Colusi Co. (by election and by appointment), he had officiated as Judge of Probate, County Treasurer, County surveyor, County Clerk, County Recorder and County Commissioner. The William B. Ide Adobe State Historic Park in Red Bluff stands as a memorial to his contribution to the area.

Suggested reading for more detailed information:

The Men of the Bear Flag Revolt,

by Barbara R. Warner, Arthur H. Clark Publishing Co.